A multi-disciplinary project connecting arts- and science-based approaches to addressing the urgent problem of population decline for the burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia).

In February 2023, faculty, students, and administration from the University of Waterloo (UW) and Arizona State University (ASU) collaborated with conservationists from Wild at Heart in Arizona to think through the challenges of rehoming burrowing owls at ASU. Through meetings with critical stakeholders, workshops on unmapping and value sensitive design, and burrowing owl habitat site visits, a living lab was established to investigate and rehabilitate existing (but vacant) burrowing owl habitats on the ASU Polytechnic campus.

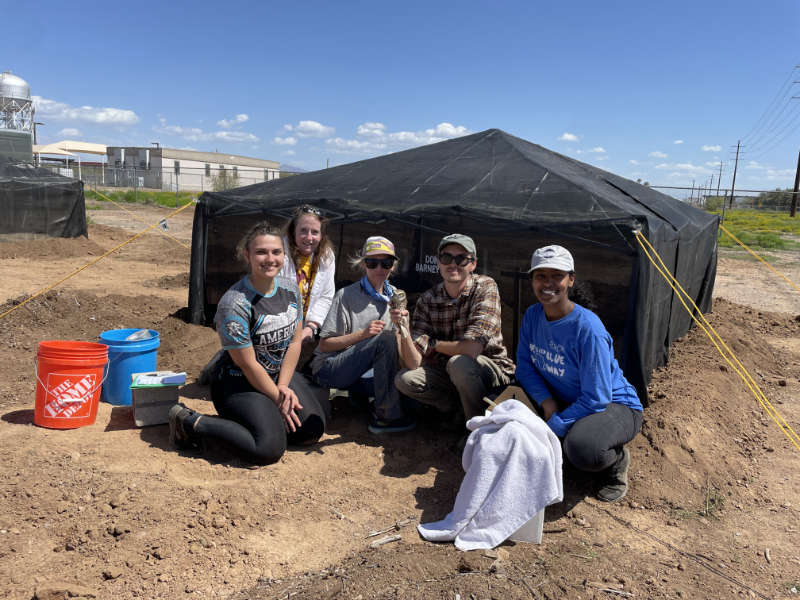

In March 2023, led by Wild at Heart, members of the ASU Polytechnic community renovated and readied the campus site for the rehoming of new burrowing owls.

Volunteers and conservationists from Wild at Heart install protective tents for newly rehomed burrowing owls in March 2023. Photos by Maureen Roen/ASU

Through this website, we encourage you to explore and engage with different perspectives on burrowing owl conservation that guide this ongoing project. Pick a section to jump to or scroll through the project in order.

Owly Infrastructure ↗

The plight of the burrowing owl, its broken habitat, and artificial burrows.

Mapping and Unmapping ↗

Get a deeper understanding of the places owls choose to nest.

Multi-species Interfaces ↗

How do you design an interface for more than humans?

Presence/Absence ↗

Accounting for burrowing owls when they’re visible and when they’re not.

Or, jump to the next section.

Artificial Habitats

Owly Infrastructure.

As their name suggests, burrowing owls nest in underground burrows typically dug by small mammals like ground squirrels, foxes, and badgers (although they are also capable of digging their own). In many parts of its migratory range, including Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Central America, the burrowing owl is listed as endangered, threatened, or a species of special concern. For burrowing owls, population decline is a complex problem but is closely related to habitat loss due to similar reported declines in burrowing mammals, compounded by human encroachment.

To mitigate the loss of burrowing owl habitats, humans have devised a variety of artificial burrow designs to mimic and act as stand-ins for naturally dug burrows. Typically, these designs comprise of large pails or drums that act as the nest space, connected to plastic tubing, which is reinforced at the entrances to prevent predators from entering or destroying the burrow.

Burrowing owls must navigate a broken habitat. As a migratory species, burrowing owls are subject to different regulations as they cross human-made political borders throughout its range. This creates challenges for conservation efforts as the burrowing owls may face different levels of protection depending on where they are situated.

Designing burrowing owl habitat mitigations requires combining local knowledge of the environment with an understanding of burrowing owl needs, while negotiating with stakeholders to determine suitable spaces for burrows will be installed.

owly spaces

Mapping and Unmapping.

Tending to burrowing owl habitats means pursuing a deeper understanding of the spaces owls choose to nest.

Although they seem like an unlikely pair, burrowing owls and humans often live in close quarters. Because burrowing owls spend so much time on the ground, they prefer clear areas without many spaces like trees for potential predator birds to perch or large shrubs and plants where land-based predators can hide. This means burrowing owls sometimes find homes on the edges of farms or, in cities around clear lots. But as urban areas continue to expand, burrowing owls frequently find themselves in the path of developers. In jurisdictions like Arizona, burrowing owls are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and under state laws that dictate how contact with the birds must be handled and in many cases, how and where burrowing owls are relocated.

While there are many examples of burrowing owls being removed from their chosen nesting location, there are also instances of artificial burrow sites being installed in suitable urban and rural locations to rehome owls that would be otherwise displaced. Planning burrowing owl nesting spaces both in built environments like a university campus or in more remote locations like farm fields necessitates thinking through how humans live with nonhuman others.

Questions for thinking through relations

Seeing and working with burrowing owl nesting sites requires understanding spaces as multi-layered.

Instead of working with spaces through literal mapping practices, these questions invite reflection on how to life with nonhuman others. Using the categories below as examples, image how thinking through each layer enable humans to think relationally, especially when devising conservation strategies.

History

Who were the first people to live in the area? Who has settled there since? How has the space changed over time? What expectations are there for the future of the site?

Culture

What are the beliefs, values, and customs of the people who share a space? What tensions might exist between humans and nonhumans?

Landscape

What is the environment of the site? What does the ground feel like, how wet or dry is the soil? What is underground? What built elements are present in and around the site?

Habitat

What other plants and animals, and other nonhuman life share the space? How do connections with other layers change habitat conditions from year to year.

Stakeholders

Multi-species Interfaces.

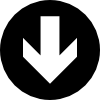

Working with burrowing owls, like working with any nonhuman species, involves constant negotiation: human-bird negotiation, institutional-conservation negotiation, owl-policy negotiation. Navigating these relationships is rarely straightforward as disagreements, conflicts, and tensions inevitably crop up. As humans attempt to create meaningful acts of conservation, it can be helpful to think through tensions that exist between the multitude of stakeholders encompassed by a project by reflecting on their values and attempting to identify tensions and ways those conflicts could be resolved.

What do values have to do with interfaces?

Like the example of mapping and unmapping above, thinking about values, especially the values of owls and other nonhuman stakeholders, can lead to new ways to engage in and imagine conservation practices that decenter humans and their needs. Decentering human values does not mean ignoring, in this case it is a way of reframing a problem that invites new ways of imagining how humans might interact with burrowing owls to foster interest, education, and attention to their plight.

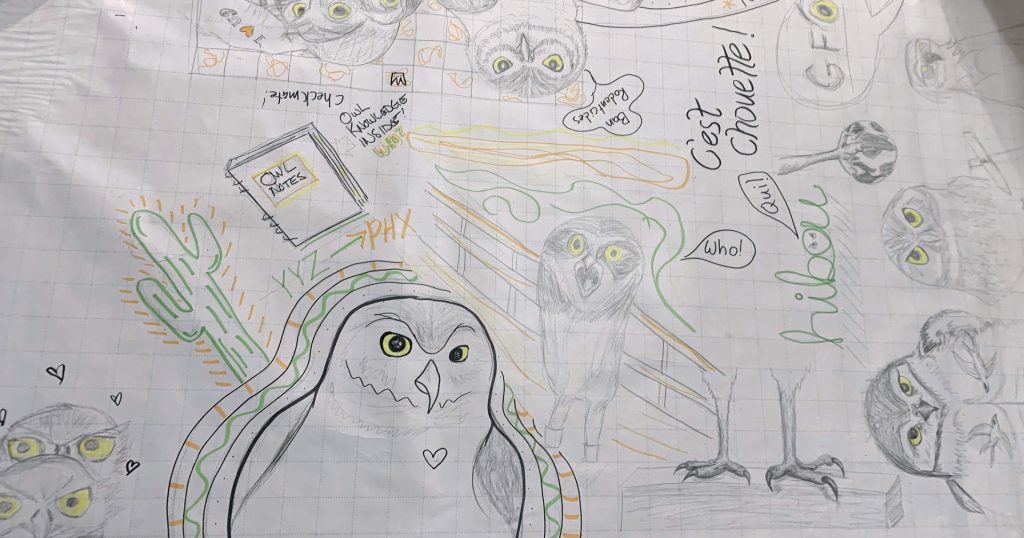

When you think about interfaces you might think about a smartphone touchscreen, but what about an educational sign at a park, or a poster in your school hallway? This project workshopped with user-experience (UX) students at ASU how they might design interfaces that account for values outside of their own.

Working in groups, students imagined augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR) interfaces through which visitors experience burrowing owl rehoming sites. Students envisioned AR experiences where visitors could get an “owl’s-eye view” of a burrow or get a first-hand feel for the values of a burrowing owl. Of course, thinking through values means negotiating and students also came up with ways to monetize and encourage more interest in burrowing owl conservation.

Defining success

Presence/Absence.

Seeing burrowing owls at a site with artificial burrows is exciting! It makes humans feel good about conservation efforts like relocation.

But what happens when burrowing owls are not present?

Through research and trial and error, burrowing owl rehoming projects using artificial burrows can be extremely successful in a traditional sense, with owls taking to artificial burrows and even attracting outside owls, creating sites with large or long-term owl populations. But not all artificial burrows attract burrowing owls and not all burrowing owls stay when they’re rehomed.

Although burrowing owls certainly have a charisma that makes them impactful for humans to encounter, this project also works with questions of absence. This type of attunement to what is not visible asks what can humans learn when owls are not present, and should a site be considered a failure if burrowing owls abandon an artificial burrow?

Thinking through the presence and absence of burrowing owls invites reflection on the spaces humans share with these birds. Regardless of how threatened a burrowing owl’s population is classified in a given place, pursuing places of presence and absence figures how hopeful and helpful thinking about conservation and species at risk can come from investigating spaces where burrowing owls make their homes and the spaces they have abandoned.

Return to the beginning of the project.